Schwimmen mit dem größten Fisch im Meer …

Walhaie – Was für schöne und geheimnisvolle Tiere. Mich haben diese Kreaturen schon immer fasziniert. Mitte 2013 wurde die Idee mit Walhaien zu schwimmen geboren und ich begann sofort mit meinen Recherchen. Obwohl es auf der ganzen Welt verschiedene Orte gibt, an denen man sie findet, war das Ningaloo Reef an der Westküste Australiens schon bald mein bevorzugtes Ziel. Man kann also sagen, dass Walhaie der Hauptgrund waren, warum ich mich entschieden habe wieder nach Australien zu gehen. Zumal ich dort auch die Chance hatte, riesige Manta-Rochen zu sehen, denn Manta-Rochen ziehen zu dieser Jahreszeit an der australischen Westküste nach Norden, während die Walhaie nach Süden ziehen.

Der Ort war festgelegt und auch die Zeit: der gesamte Juni 2014. Das Komische war, dass niemand um mich herum meine Pläne bis Mai 2014 ernst genommen hat, sondern erst als die letzten Vorbereitungen für diese Reise auf Hochtouren liefen.

Der Flug mit emirates von Düsseldorf über Dubai nach Perth war wirklich angenehm. Als ich um 00:30 Uhr in Perth ankam, wartete mein lieber australischer Freund bereits am Flughafen auf mich, um mich abzuholen. Kurze Fahrt zum Hotel, das im Zentrum von Perth lag. Einchecken. Duschen. Schlafen.

Am nächsten Morgen wachte ich erfrischt auf und war bereit, das neue Abenteuer zu beginnen. Es fühlte sich so gut an, wieder in Australien zu sein, aber dieses Mal fühlte es sich weniger “fremd” an, verglichen mit dem letzten Mal, als ich hier war. Das Gegenteil war der Fall. Alles war so vertraut und überall, wo ich war, fühlte ich mich wohl und zu Hause. Ein wirklich angenehmer Gemütszustand, wie Sie sich vorstellen können.

Als erstes mussten wir unser Gefährt abholen. Ein Campervan, der meine Erwartungen definitiv übertroffen hat und “Haus auf Rädern” heißen sollte. Nicht zu schlecht für zwei Personen. Es bot unter anderem zwei Full-Kingsize-Betten, Backofen, Herd, Mikrowelle, Satellitenfernsehen, Dusche, Toilette, Waschbecken und: eine elektrische Stufe, die per Knopfdruck ausfuhr.

Dieses Gimmick sollte mein Favorit werden und ein lustiges Ritual werden, denn wo immer wir anhielten: Das erste, was ich tat, war

diesen dummen kleinen Schritt auszufahren und ‘Der Adler war gelandet’.

Also zunächst ein kurzer Überblick über interessante Stopps auf unserem Weg nach Exmouth:

Pinnacle National Park was the first stage on our trip all the way up to Exmouth.

An extraordinary place to visit. So unreal and calm and somehow comforting at the same time. You just have to allow the ambience to embrace you and just let go. An impact, lot of places in Australia have on me, though.

Next stop: The Pink Lake (Hutt Lagoon) at Port Gregory.

Port Gregory lies near the mouth of the Hutt River on Western Australia’s Coral Coast and is home of the Pink Lake called Hutt Lagoon. This picturesque fishing village is encircled by five kilometres of exposed coral reef. Originally developed to serve the Geraldine Leadmine, the town is now a holiday hotspot for fishing, diving and offers a range of accommodation options.

Hutt Lagoon boasts a pink hue created by presence of carotenoid-producing algae Dunaliella salina, a source of ß-carotene, a food-colouring agent and source of vitamin A. Depending on the time of day, time of year and the amount of cloud cover, the lake changes through the spectrum of red to bubble-gum pink to a lilac purple. The best time of day to visit is mid-morning or sundown. Hutt Lagoon can be easily accessed by road along the George Grey Drive, between Geraldton and Kalbarri.

The lagoon is about 70 square kilometres with most of it lying a few metres below sea level. It is separated from the Indian Ocean by a beach barrier ridge and barrier dune system. Similar to Lake MacLeod, 40 kilometres to the north of Carnarvon, Hutt Lagoon is fed by marine waters through springs.

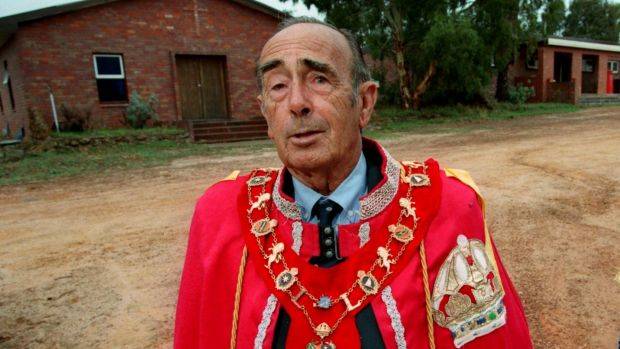

At the Principality of Hutt River – a micronation in Australia – we met our incredible friendly host for a day: Leonard (Leonard George Casley).

The principality claims to be an independent sovereign state, founded on 21 April 1970. The territory is located 517 km north of Perth, near the town of Northampton in the state of Western Australia. It has an area of 75 square kilometres, making it larger than several independent countries.

The principality is a regional tourist attraction and issues its own currency, stamps and passports (which are not recognised by the Australian government or any other government). The Australian Postal Corporation deliveres letters with Hutt River stamps on them, though.

If you would like to know more about Leonard George Casely and the origins of the Principality of Hutt River, please check this article on Wikipedia.

Exmouth

The great moment was within reach. I thought nothing would be so cool like this one here, but Dancing Manta Rays and White Sharks are in the same league.

But let’s focus on Whale Sharks again. The evening before, we double checked our gear, prepared the cameras and packed our bags for the following day. Early next morning we were waiting for the bus to pick us up at the main entrance of the campingground. The weather was perfect and everything was set to make this a great day.

At the pier we were welcomed and we got onto the boat. MJ and all the others from 3 Island did an outstanding job and made it a perfect day – and believe me, I rarely use this superlative. They were friendly, caring, competent, professional and made this an awesome experience.

Tour Itinerary 3-Island-Whale-Shark-Dive

Your day starts at approximately 7.15am when the Three Islands’ air conditioned courtesy bus picks you up from your Exmouth accommodation for the 36 kilometre journey to the Tantabiddi Boat Ramp departure point. During the drive to Tantabiddi, an informative and factual commentary on local points of interest is given, including the Cape Range National Park. The day’s program is also outlined, helping to ensure you feel relaxed, informed and comfortable about the upcoming day’s events. From the boat ramp you are transferred to the 17 metre “Draw Card”. Once on board, wetsuits and snorkel equipment are fitted, the crew are introduced and a vessel safety brief is given. A short cruise through the lagoon and the marine adventure begins with an introductory snorkel on the beautiful inner Ningaloo Reef.

Dies ist die Überschrift

If required, assistance and snorkel tuition can be provided by your tour guides. Have the chance to see a turtle swim past, a ray resting in the sand and a myriad of colourful fish amongst the coral.

Dies ist die Überschrift

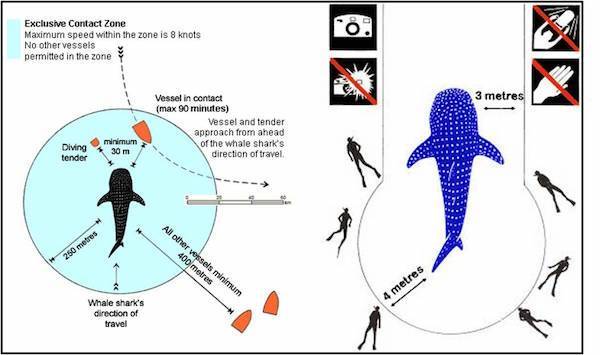

Following the morning snorkel, a whale shark interaction briefing is given over morning tea where the code of conduct is explained by one of your guides.

Dies ist die Überschrift

At the conclusion of the brief the vessel fires into life and you can feel the anticipation build as we head to the outer reef waiting for the spotter plane to notify us that a whale shark has been found.

The radio crackles and the adventure is about to begin, the deck starts to buzz as the crew and passengers get ready. A mix of sheer excitement with a hint of apprehension is visible on even the most experienced swimmers’ faces. “What am I about to do? I’m jumping in the ocean with the world’s biggest fish!?” As the skipper lines up the boat, what awaits our first group of swimmers? Faces down, you see it emerging from the distance with it massive mouth wide open, as it gets closer and swims past, apprehension becomes amazement and the excitement builds as you swim along with your own big spotty fish! Groups are rotated through the water to snorkel alongside; always with the company safety zodiac following behind if anyone requires assistance. Guests often let out a cheer while waiting to be picked up, ready to do it again and again. Our photographer is always there capturing images and moments that will long be remembered for the complimentary CD. Alternatively BYO USB or request a download link emailed to you. During all the excitement, a delicious lunch is served buffet style. If time permits, we head back to the inner reef to conclude the day with a reef snorkel. You may have the opportunity to swim with manta rays if spotted (from late May) and see humpback whales from the boat (from late June). A fruit and cheese platter finishes off the day, with a complimentary beer and champagne as we cruise back to the boat ramp, and then back home to your accommodation.

"Don't swim in front of them, they might get scared"

Yeah, like the Whale Shark is the one to be scared. Not to swim in front of a Whale Shark sounds easier than it was, by the way. Especially if the Whale Shark got interested in my yellow fins. Swimming next to me, MJ giggled and said it apparently wants to play with me. Instantly the three standard german dog owner phrases popped into my head.

1. “Der tut nix!” – “My dog means no harm.”

2. “Der will nur spielen.” – “It just wants to play.”

3. “Das hat er ja noch nie gemacht.” – “It hasn’t done that before.” (Usually said after it DID harm in any way)

So I swam to the right to give way – and it followed. I swam to the left – and it followed. Ok, perhaps further left? – Nah, still following. Well, then right again – and it followed and closed in, so I was brushing its snout with the tip of my fins. At that point I noticed I did not enough cardio in the past.

Finally the Whale Shark lost interest and I unintentionally celebrated that immediately with some gulps of seawater. With that overdose of salt, the only thing missing was the tequila and lime. Back on the vessel the skipper did not have any of that, but he offered me some candied ginger instead – which I discovered to be my eject button …

Problem solved and I got back my sanguine complexion again and felt better immediately. Just in time to get into the water again for my next encounter!

Scientific background on whale sharks

Despite their huge size, whale sharks are docile, filter feeders that cruise the world’s oceans looking for plankton. These gentle giants are famous for their annual gathering at WA’s Ningaloo Reef, but outside these waters very little is known about this threatened species, which is considered as globally vulnerable.

Andrew Smith was the first Ichthyologist, to describe and name the whale shark back in 1828.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are found throughout the world’s tropical and warm, temperate seas. They are known to inhabit both deep and shallow coastal waters and the lagoons of coral islets and reefs, and prefer surface seawater temperatures of 21 – 25 degrees Celsius. Whale sharks occur throughout the Indian Ocean and have also been reported near the Maldives, Seychelles and Comoros Islands, and along the coastlines of Madagascar, Mozambique, Kenya, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia.

This species is widely distributed in Australian waters, found mainly off northern Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and Queensland, with isolated reports of sightings from Victoria and New South Wales.

Not much is known about the migration of whale sharks except that they can travel thousands of kilometres a year, and over the years have become famous for their aggregation every spring at the continental shelf of the central west coast of Australia. Here they are most common at Ningaloo Marine Park, off Exmouth and Coral Bay, but they also appear at Christmas Island and in the Coral Sea.

A shark, not a whale

A whale shark is a fish and breathes via its gills.

The name whale shark comes from the fact these animals are so large (as big as whales) and that they filter feed (like baleen whales such as the humpback). However, they have cartilage instead of bone – making them a true shark.

The whale shark is the largest living shark. It is the only member of the Rhinocodontidae family. Like many other sharks, whale sharks have biological characteristics such as large size, slow growth, late maturation and longevity that, despite an ability to carry large numbers of embryos, can impact upon their numbers. These characteristics, together with the species’ naturally low abundance, make whale shark populations highly susceptible to over-exploitation.

Whale sharks are the largest fish in the ocean, usually growing to 12 metres in length, although a fully-grown whale shark can reach up to an incredible 20 metres long and weigh 20 tonnes. These giant animals are easily recognised by a distinctive pattern of white spots and stripes on a dark bluish-grey background. Their undersurface tends to be pale, with no markings. The patterning helps them blend into their environment and is unique to each individual, which can be useful when researchers are counting populations.

Filter feeders

The head of the whale shark is different in shape from most other sharks, being characteristically very broad and square. They have two small eyes situated towards the front of the head and an extremely wide mouth, up to a metre across. The mouth of a whale shark contains over 3,000 tiny teeth arranged in more than 300 rows, however, they neither bite nor chew their food. Despite their huge size, these gentle giants are in fact filter feeders – one of only three known filter feeding shark species (the basking shark and the megamouth shark being the others).

Whale sharks feed on minute, planktonic organisms including krill, jellyfish and crab larvae, which are strained from the water through the shark’s gills by a fine mesh of gill rakers. Whale sharks filter large quantities of seawater either by actively sucking water into their mouths, or by cruising along near the surface of the water with their large mouths agape as they look for plankton. Whale sharks must consume large quantities of these small animals in order to survive. They also supplement their diet with larger prey such as squid or small fish including sardines, small tunas and anchovies. Sensory cells in the nasal grooves above the mouth help the shark detect food in the water. It is thought that whale shark movement patterns are linked with spawning of coral and plankton blooms, which probably explains the annual appearance of whale sharks to Ningaloo Reef following the mass spawning of coral each year in these waters.

With eyes that are set far back on its head, the whale shark doesn’t rely much on vision to find the most plentiful feeding ground. Researchers believe that it uses its sense of smell to locate the most protein-rich waters — its nostrils are conveniently located near the top of its wide mouth. These creatures like to feed in the evenings near the ocean surface where krill and shrimp are abundant.

A mysterious life cycle

Little is still known about the whale shark’s life cycle or exactly how long they live. It is estimated that whale sharks may live to over 100 years of age, reaching maturity at around 30 years. They are thought to have a fast growth rate when very young, which then slows down, taking them a long time to reach maturity and adding to the vulnerability of this iconic species.

Like all shark species, male whale sharks can be distinguished by the presence of two claspers near the pelvic fin, which are absent in females. Whale sharks are extremely difficult to age, but evidence suggests that both sexes may reach sexually maturity when they are around eight or nine metres in length. The size of maturity of female whale sharks cannot be determined through external observation.

Until 1995, researchers knew little about the reproductive cycle of the whale shark. Many experts thought that the large shark was oviparous, meaning that it laid eggs on the ocean floor. But in 1995, a large female whale shark was captured and observed.

Female sharks give birth to fully-formed live young that develop from eggs in the mothers’ uteri prior to birth, making it ovoviviparous. About 300 young are born, between 40 and 70 cm in length, after an unknown gestation period.

The first documented capture of a pregnant female whale shark was off the coast of Taiwan, which was found to be carrying 300 ‘pups’.

Since research on these big fish is scarce, we aren’t sure exactly how long whale sharks live. But sharks are notoriously long-living fish, and the whale shark’s size indicates it may live up to 100 years.

Humans a major threat

There are very few known predators of the whale shark,although blue marlin and blue sharks sometimes prey upon small individuals. The most significant threat to this species appears to be humans. Whale sharks’ large size, slow speed and habit of swimming at the surface (although they dive to depths of over 1,500metres), makes them easy to kill. Although their skin can be up to 14 cm thick, they are still vulnerable to fishing and injury from boats. Even floating plastic rubbish they may swallow can cause injury or lead to death.

Unfortunately this species is hunted in some parts of its range for its flesh, liver oil, cartilage and fins, which have become increasingly popular for use in shark-fin soup. Due to their relatively large size, whale sharks’ fins are sold for very high prices and there is still a market for whale shark meat in several countries, including China and Taiwan.

Ecotourism

Despite their size, whale sharks do not pose significant danger to humans. They are gentle, docile creatures that are at times playful and curious. Snorkellers swim with these giant fish without real risk, apart from the chance of an unintentional blow from the shark’s large tail fin.

Opportunities to swim with these fascinating creatures have led to the development of an increasingly popular, seasonal ecotourism industry, particularly in Western Australia where these sharks have become a huge tourist attraction at Ningaloo Reef and, to a lesser extent, at Christmas Island. Every year from April to July following the mass spawning of coral, the world’s biggest fish congregates in the Ningaloo Marine Park. Visitors from all over the world now head to the Ningaloo Reef during whale shark season to experience the exhilaration of snorkelling with them.

The coral spawning at Ningaloo Reef provides whale sharks with an abundant supply of plankton and tropical krill, with unique current systems off WA helping to keep this food supply close to the coast, where the sharks are easily accessible to observers.

The predictability of the occurrence of Whale sharks at Ningaloo has been important to the development of the ecotourism industry in the area. This industry is carefully managed through a system of regulations, including the licensing of a limited number of tour operators and codes of conduct. There are very few known predators of the whale shark, although blue marlin and blue sharks sometimes prey upon small individuals. The most significant threat to this species appears to be humans.

Whale sharks’ large size, slow speed and habit of swimming at the surface (although they dive to depths of over 1,500 metres), makes them easy to kill. Although their skin can be up to 14 cm thick, they are still vulnerable to fishing and injury from boats. Even floating plastic rubbish they may swallow can cause injury or lead to death.

Unfortunately this species is hunted in some parts of its range for its flesh, liver oil, cartilage and fins, which have become increasingly popular for use in shark-fin soup. Due to their relatively large size, whale sharks’ fins are sold for very high apply to people swimming with whale sharks and vessels operating in the vicinity of them. Whale shark ecotourism is well managed in Western Australia via a collaborative approach between industry and the Department of Environment and Conservation. Professional charter boat operators in places such as Coral Bay and Exmouth offer day tours and will inform you about the best way to observe these animals with minimal disturbance.

Whale sharks have been observed to react to SCUBA bubbles, touching and flash photography so these activities are not permitted when swimming with whale sharks in Western Australia. When these guidelines are adhered to, whale sharks do not seem to be affected by the presence of humans. With the rise in passenger numbers, it is becoming more important to observe these rules and regulations so that the increasing number of encounters does not have a negative impact on the sharks. The WA codes of conduct are ensuring the whale sharks are protected but can still be admired in a non-detrimental way – and are now being adopted in other parts of the world as an example of ‘best practice’ management.

The ecotourism industry’s interaction with whale sharks provides useful information that is passed on to scientists so they can better understand these gentle giants, and further educate people about them.

Protecting the world’s largest fish

The whale shark is identified as a migratory species under the International Convention on Migratory Species. Whale sharks are protected throughout Australian Commonwealth waters under fully protected in Western Australia under the Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 and the Fish Resource Management Act 1994. Therefore, it is an offence to disturb, harm or fish for whale sharks in any way.

Although whale sharks are considered as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), there are still several locations where unregulated fishing and hunting for whale sharks occurs.

This species is only protected in around 13 of over the 100 countries that it is known to visit, including Australia, United States of America, India and the Philippines. Work continues to achieve protection in other countries that still permit the hunting of whale sharks.

Improved knowledge of the movement patterns of these sharks will help in the management and conservation of this species. Satellite tracking has been attempted for a number of years off Ningaloo, owing to concerns that fisheries north of Australia that exploit whale sharks may impact on the number of sharks that visit Western Australia each year. Tracking whale sharks that have been fitted with acoustic transmitters is another method that marine scientists have used to try and gather more information about whale shark movements and feeding patterns.

More information is required to better protect these animals and, thanks to a thriving ecotourism industry in WA, more and more is being learnt about these majestic animals every year.

Australia plays an important role in the conservation and protection of this migratory species. Ningaloo Reef Marine Park represents one of the few strongholds in the world for this magnificent, gentle giant of the deep.

References

Websites:

CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research

Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia

Department of Fisheries, Western Australia

Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities

Exmouth Visitor Centre, Western Australia

Marine WATERs, Western Australia

Articles and papers:

Anderson, C. 2008. Spotting the biggest shark.

Western Fisheries, WA’s Journal of Fishing and the Aquatic Environment.

Department of the Environment and Heritage. 2005.

Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus) Recovery Plan Issues Paper. Canberra, ACT. Australia.

Julian, C. 2006. Stars in the Sea. Western Fisheries, WA’s Journal of Fishing and the Aquatic Environment.

Storrie, A. and Morrison, S. 1998. The Marine Life of Ningaloo Marine Park and Coral Bay.

Department of Conservation and Land Management.

Books:

Last, P. R. and Stevens, J. D. 2009.

Sharks and Rays of Australia. 2nd edition.

CSIRO publishing. Collingwood, Australia.